3. Guest Composer Residencies and Horse Poop (March 2018)

Tuesday, March 27, 2018 at 12:27PM Comments Off

Tuesday, March 27, 2018 at 12:27PM Comments Off I just finished three guest composer residencies over five weeks:

Andrew Boss, Jennifer Jolley, Patrick Dunnigan, John Mackey, and Kim Archer at the 2018 CBDNA Southern Regional Convention1. A CBDNA Southern Region performance of Common Threads (Florida State University Symphoic band in Tampa, FL),

Andrew Boss, Jennifer Jolley, Patrick Dunnigan, John Mackey, and Kim Archer at the 2018 CBDNA Southern Regional Convention1. A CBDNA Southern Region performance of Common Threads (Florida State University Symphoic band in Tampa, FL),

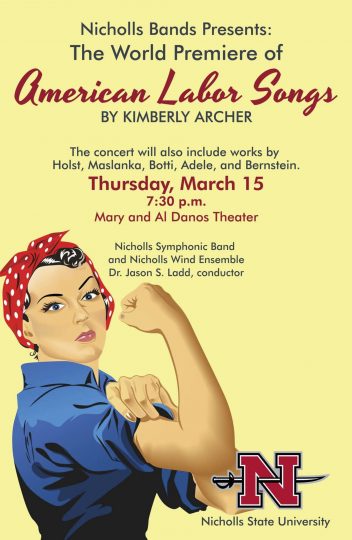

2. The world premiere of American Labor Songs (Nicholls State University Wind Ensemble in Thibodaux, LA), and

3. The world premiere of The Pipers (Desert Winds Freedom Band in Palm Springs, CA).

It was all intense, emotional work, where I made new friends and the music roared into life. It’s like giving birth but without all the screaming and messy goo.

Artist residencies are fun but even after two decades, my family and faculty colleagues don’t exactly understand what this means. They note that I go away for a few days, then abruptly either go radio silent for several more days after I get home, or they end up wishing they’d let me stay radio silent because I’m so grouchy.

Knowing I had three trips coming in a row, I started thinking about this phenomenon. It turns out there’s nothing magical about the process and the solution for grouchiness is simple:

Horse poop.

A guest composer residency starts with going to a new place to meet strangers. I’m always nervous, even knowing conductors and bands treat composers so well – in fact, sometimes a bit like a mythical creature, since most people think of composers as dead European guys. Really, it takes about three seconds to shake hands, smile, and realize we’re all nervous but we have plenty in common as musicians. Sure, we’ll feel each other out on heavy artistic matters eventually, like favorite craft beers and whether Star Trek II or The Empire Strikes Back is the better sequel, but not right away.

Second, a residency usually involves several guest lectures and/or private lessons, and sometimes visits to local K-12 schools. Each event is akin to a traditional conference presentation, so imagine doing two or three of those in a single day! I have learned how to pace myself, eat healthy (no matter how awesome that local fried cuisine smells), conserve my energy across several days, and not be shy about asking for caffeine or escaping to the restroom, if only to have a few moments to myself.

Second, a residency usually involves several guest lectures and/or private lessons, and sometimes visits to local K-12 schools. Each event is akin to a traditional conference presentation, so imagine doing two or three of those in a single day! I have learned how to pace myself, eat healthy (no matter how awesome that local fried cuisine smells), conserve my energy across several days, and not be shy about asking for caffeine or escaping to the restroom, if only to have a few moments to myself.

These events are also rare opportunities to speak on topics that don’t come up in day-to-day teaching. What a treat! People actually want to hear about the Scottish history that attracted me to the traditional bagpipe music I studied in order to recreate an authentic sound with a concert band. They want to know what I think about musical form in the modern era. They want to hear my stories about other composers and the time I sat down in the wrong seat, next to strangers, after speaking to an audience. Practically never does anyone at home want to know what I think! Also, if I accidentally say something dumb at home, I can be sure someone will call me on it, but guest artists have diplomatic immunity.

Third, people used to believe that composers were too busy listening to the Muses to match their socks or brush their hair. The bar for graceful sociability is a lot higher now. As a shy introvert (honestly), it’s sometimes challenging. I can talk forever – after all, I’m a professor – but it’s still quite different from my normal solitary routine. On the other hand, it’s so worth it because there is always something for which I’m needed in these new places. There’s always a bigger reason why I’m there, even if it takes me a while to figure it out. There’s a student or colleague who needs affirmation or rejuvenation, or the ensemble doesn’t yet realize how much more it can accomplish and needs help to negotiate the next step.

There’s often a little tension when I arrive, too, partly because I’m a stranger but also because my music is challenging. I’ve heard a lot of, “We didn’t like this music at first but then we got into it and it grew on us. It’s so cool! But … you know it’s hard, right?” I used to get defensive about it, but the truth is performers and conductors pretty much always rise to the challenge. Having the composer in residence almost always results in a particularly powerful performance, too, and then the conductor and ensemble are stunned by it – elated after conquering frustration or maybe fear. I’m not saying every performance is perfect, only that growth and courage are so much more interesting and important. I think sometimes people invite composers because they need our encouragement – permission – to stretch. And potentially not succeed, right? That’s the risk, but the most important part is to give a full intent of trying.

Courage changes people; it changes the world; it changes me. By now, I trust growth and courage can happen, will happen, and intuitively feel my responsibility to facilitate it in the guest artist process. It’s an intense, patient act of faith every single time.

And the payoff!

I once worked with a conductor in personal crisis who was ready to leave the profession. He thought our collaboration might be his last performance and told me how difficult rehearsals had been. We worked together to reassure his band, as well as reassure him, that they had all done impeccable preparation, that their music making was strong and good. Just believe, just go for it! After a hot, wonderful concert, this conductor talked about building an entire concert theme around another work which had touched him. He almost began to cry and blurted out, “I haven’t wanted to do this in such a long time!” His musicians needed him to pass through his darkness and rejoin them. He needed to see that he could go on and reclaim the joy in music making. Maybe he was ready anyway, or maybe my being there had something to do with this – if so, it’s an honor to be of service in this way. It feels Good.

Then there’s the music.

Waiting in the hall before the first rehearsal, there’s nothing more flattering than hearing performers practice passages from my music. I sit off to the side and play it cool, don’t watch too closely, like I don’t notice, but it’s one of the best parts of being a composer: someone thinks enough of my music to practice it! It’s an appetizer or a first kiss.

The ensemble has been waiting to show off. Probably this visit has been hyped up, so although it’s a rehearsal, it’s also almost a concert by itself. They want to play for me and I want to hear it. It’s fun to note who sneaks a look over their stand to watch my reactions vs. who’s too shy to risk eye contact.

The first complete run-through, if I’ve never heard the piece before, is amazing in that I may have written the piece weeks, months, or years ago, and then it finally bursts from its cocoon inside my head to become real sound. Maybe this seems strange, but music is different from other arts. When someone paints a picture, you see it immediately. When someone writes a book, you can read and discuss it immediately. But when a composer writes music, it goes like this:

1. Write the music, alone.

1. Write the music, alone.

2. Find a conductor who’s interested in performing the music, which means devoting their rehearsal time (their “curriculum”) and their own artistic efforts.

3. Extract each individual player’s part from the whole score and make each part look impeccable. (usually 30+ parts, 2-6 pages each)

4. Answer questions that come up early on, like “Could you check if this note is correct?” or “Are you sure it should be so fast?” (always blame the notation software)

5. If invited, travel to where those rehearsals are happening. (see above)

6. Finally hear the music, first in some level of preparation.

7. Help the ensemble rehearse. (could take days or weeks)

8. Finally put on a performance for others to hear.

Clinics, lectures, and lessons can be fatiguing no matter how much fun, but rehearsals are totally exhilarating. Even if it’s a work I’ve heard before, it’s like reconnecting with an old friend after years apart. Have they lost weight, changed their hair, gotten married? Good music morphs to fit each context and every band has its own sound and interpretation.

Once the performance happens, I can never hear a recording of the concert the same way I heard it live. Composer, conductor, and ensemble work together intensely. At the concert, it’s like looking at two overlapping X-rays. I remember where we started, but also see how this one passage, here, sings out now, or how that tough lick, there, came together so well, or that soloist really blossomed with confidence after a few run-throughs. Energy radiates off the stage when the performers and the conductor are having fun and working hard, smiling, attuned to all the details, and when the audience has been drawn into full attention with them. It doesn’t translate to recording but it’s shimmery and resonant and unforgettable if you were there.

Then, everyone’s emotions are flying around afterward and it can be overwhelming: OMG, THE PERFORMANCE ROCKED!!! It was SO MUCH BETTER than the last rehearsal!!! There’s a lot of hugging and smiling in the afterglow. There’s an intimacy to the whole experience and a lot of new Facebook friends. The conductor and I usually exchange emails or texts for days afterward, even about non-musical things. Having grown so close so quickly, it’s weird to separate with a snap of fingers.

It’s a big experience. It’s intense and multifaceted, both physical and emotional.

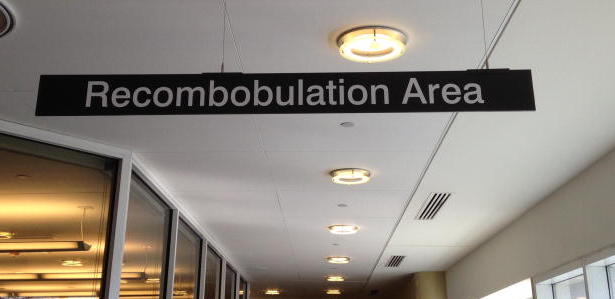

Milwaukee AirportAnd then, invariably, there’s a massive LOW when I get home. First, exhaustion. Everything aches and I can barely hold my eyelids open. There’s also mental and emotional fatigue mixed with a jarring recalibration from being an Honored Guest Composer to “plain old Kim” who teaches freshman theory in the basement of Dunham Hall to students who might not even realize I am a composer. It’s a tremendous letdown of artistic energy and focus into the pedestrian reality of grading papers and paying bills. It’s weird to drive myself in my own car again, too.

Milwaukee AirportAnd then, invariably, there’s a massive LOW when I get home. First, exhaustion. Everything aches and I can barely hold my eyelids open. There’s also mental and emotional fatigue mixed with a jarring recalibration from being an Honored Guest Composer to “plain old Kim” who teaches freshman theory in the basement of Dunham Hall to students who might not even realize I am a composer. It’s a tremendous letdown of artistic energy and focus into the pedestrian reality of grading papers and paying bills. It’s weird to drive myself in my own car again, too.

My family says they can set their watches by this cycle: I’ll go away, send epic, excited emails and Facebook posts, then come home to days of abrupt, utter silence. They know I’m face-planted on my couch, narcoleptic – and oh my, the depression lingers long after the aches and fatigue subside. Sometimes I even get sick with a minor bug that I could've faught off under normal circumstances. Then I complain about my day job, let things get under my skin too easily, and neglect housekeeping and correspondence. It isn’t safe to be around me again for at least 3-4 days.

David Maslanka used to tell me if I did a better job managing the highs, the lows wouldn't knock me over, either. What would be the point of not fully enjoying the highs?, I used to wonder. Composing is hard, frustrating work – the highs are the payoff! Anyway, it was hard to take him seriously because he so often complained, himself, of exhaustion after guest artist residencies.

Then David’s wife, Alison, told me how she learned to deal with his coming home so ego-inflated he could barely get his head through the door, followed by terrible crashes. She insisted that as soon as he put his suitcase down, he had to take the wheelbarrow out to their pasture and pick up all the poop deposited by their four horses. David smiled and shrugged when I asked him about this. It’s hard to feel like King of the World whilst holding a shovel full of horse poop, right? It reestablished normalcy for him.

I have a dog now, who celebrates my return from residencies as only a dog can. That helps. She also keeps me anchored to reality: I can’t fall into depression when she needs to be fed, walked, and played with. Still, with three residencies in a row this spring, I knew I was headed for a terrible crash. For the first time, I left myself a Horse Poop List:

I have a dog now, who celebrates my return from residencies as only a dog can. That helps. She also keeps me anchored to reality: I can’t fall into depression when she needs to be fed, walked, and played with. Still, with three residencies in a row this spring, I knew I was headed for a terrible crash. For the first time, I left myself a Horse Poop List:

- pick up prescriptions

- pay bills

- clean gutters

- change the furnace filter

- iron the laundry

I won’t even pretend I escaped the siren song of my couch, but this time I did it with my dog snuggled in my armpit and backlogged episodes of “Young Sheldon” running. I think I’ll always feel, when coming home, a little like the recruit on first leave from military boot camp: I’ve seen things, I’ve changed in powerful ways, I’m different from the people at home now. Still, home is home and life is in the horse poop. It’d be nice to live in the perpetual world of the Guest Composer, but when would I get any actual composing done?