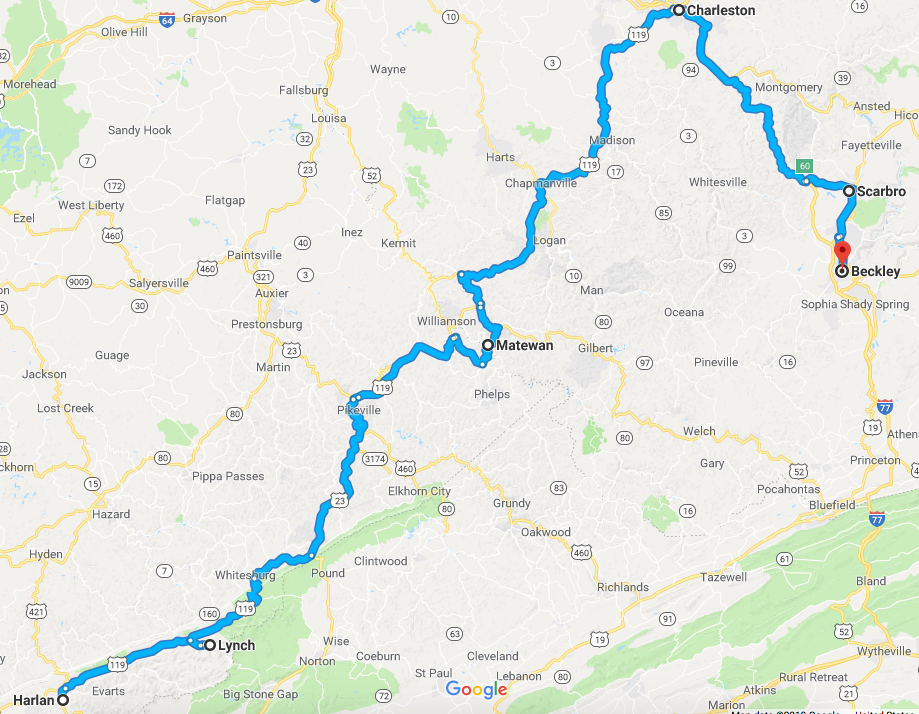

In the past ten days I’ve toured the sites of significant labor struggles of the 20th century, centered on Harlan County, Kentucky and the Charleston area of West Virginia.

For two years I’ve been an organizer and now the first president of a brand new Illinois Education Association local. The ongoing political and fiscal chaos in a state with a rabidly anti-labor governor, plus the challenges of forging a new union’s identity, had depleted me. Unions always have been an uphill battle and always will be. I know that, but this was my first time up the hill. I wanted to reconnect with my historic roots as a union organizer and officer. I needed a visceral reminder of why we do this, as well as a reality check about how much others sacrificed to get us this far.

I’d written “this month in labor history” stories for our local’s newsletter, mostly about coalminers. The feedback was, “You know college professors aren’t anything like coalminers, right?” From a philosophical perspective, I'm not so sure. Of course teachers’ work is a universe different from the physical dangers of mining. Still, don’t we all want the same basic things, even if we experience the world on different points of a continuum?

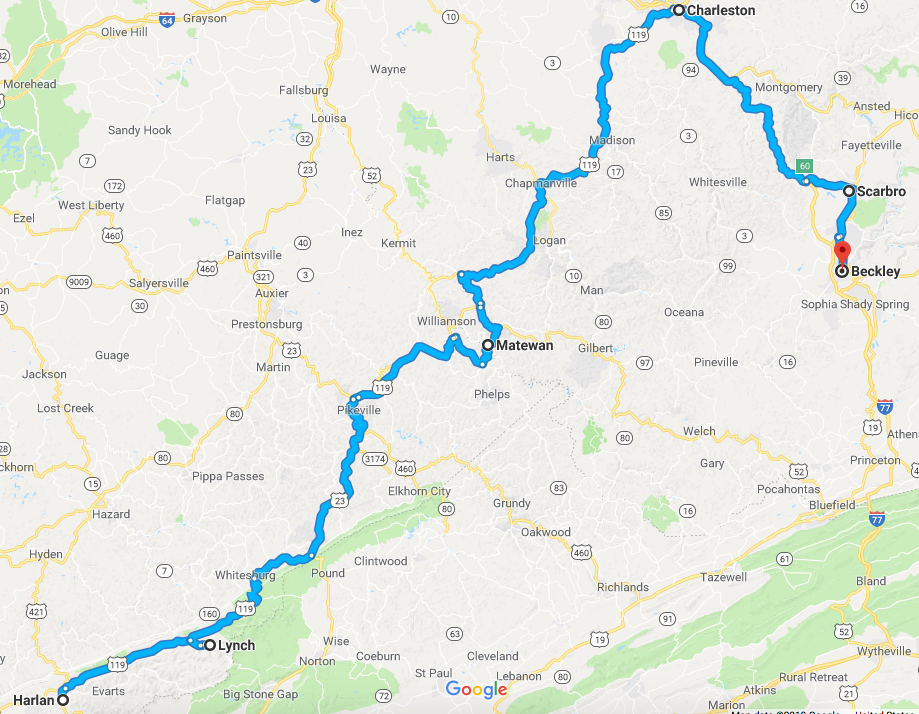

Before I left, I researched “Bloody Harlan” of the 1930s, the Brookside strike of 1973-74, the Matewan Massacre of 1920, and the West Virginia Mine Wars. I used my National Education Association (NEA) benefits to book hotels. Then the dog and I set out.

First stop: Mt. Olive, Illinois where Mother Jones is buried. I opened a bottle of Bushmill’s and poured a ceremonial first shot on Mother’s grave, reciting, “Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.” I had a shot, too, and the dog sniffed the glass. From then on we poured a shot for Mother Jones everywhere we stopped – on a UMWA site when we could

“They say in Harlan County, there are no neutrals there.”

- Florence Reese, “Which Side Are You On?”

Brookside, KY

I had mixed feelings about visiting Harlan County. The miners won their two famous battles there but they were indeed violent and prolonged.

In short, the coal company was headquartered in the Carolinas and feared that if unionism (deliberately, incorrectly equated with communism) took hold in Kentucky it would metastasize to their base of operations. To management, surely that was a threat which justified ruthlessness and callous indifference to humanity – a threat which justified anything at all to preserve their wealth and domination over their seeming herds of cheap, replaceable labor.

The mining community in Harlan thought otherwise and didn't stand for it.

Twice.

This reminded me of the first Women’s March in St. Louis after Trump was elected, where women in their 60s and 70s carried signs that read, “I can’t believe I have to protest this shit again!”

I seriously wondered if the place would feel evil. Ultimately, though, I had to go because while Mother Jones never set foot there – she died before “Bloody Harlan” began in 1930 – it was the women of the community whose bedrock resolve carried that fight both times. In fact, during the Brookside strike, wives and daughters formed the Brookside Women’s Club as an auxiliary to the United Mine Workers. They went as far as laying down in front of scabs’ cars, were shot at and jailed, and yet kept going even when it seemed the men themselves might want to give up.

These women knew what my local also discovered on the way to our first contract: public opinion and bad press can assert as much pressure on management as jackrocks and explosives.

The Brookside strike happened the year I was born. That injustice and the miners’ struggles in Harlan County are not some academic history; they are literally the world I was born into. I wanted to stand in that place, breathe that air, and perhaps draw resolve of my own from it. The film Harlan County, USA moved me deeply. It wasn’t just that film, though. I wanted to go because Harlan County has developed a mythology of grit and grassroots effectiveness in shows like Damnation, opposite a caricature of bleak economic and cultural despair in Justified. I wanted to go because powerful music emerged from that place and found its way into my imagination. I had already twice set my own versions of Harlan activist Florence Reese’s 1930s song “Which Side Are You On?”, once for band and once for choir.

There was no tremor when I crossed the county line, only a sign that read “Welcome to Harlan County, Please Don’t Litter.” The first thing I did was turn left off Route 421, the main drag, and cruise along Route 38 toward Brookside. It happened so fast I missed it and had to circle back: a little pullout to the left leading to a faded gatehouse. Far behind that, peeking out of the overgrowth, was the rusting skeleton of a tipple. The pavement had crumbled into muddy potholes, the buildings were little more than rotting wood and yellowed windows, and the place was impassible by car because of the overgrowth. The chain link fence by the gatehouse sagged and the security barrier was gone.

It’s not evil; it’s nothing. You would never guess this was the locus of so much struggle 40 years ago, nor that miners' blood ran the creek red 40 years before that. How fast the mountain reclaimed it.

Directly across the street, a sign pointed to a narrow path sloping downhill and out of sight. That had to be the site of former company housing, so I pulled in. I saw a lot of neighborhoods exactly like this in towns near the specter of a tipple: a community boxed in, literally out of sight and out of mind from the rest of the world. In this case, a railroad track ran along one long edge and a creek ran along the other, so there was no room for expansion and nowhere to hide from a “Bull Moose Special.”

The neighborhood was laid out in a grid with the aesthetic of a sardine can. A space that might have held two or three cramped Midwestern blocks instead held four long rows of single-family houses. The yards mostly served as a shoulder or parking space since two cars couldn’t pass each other on the narrow road. Adjacent families could hold a conversation through their open windows, yet it was midday and silent except for three men in jeans and white undershirts frowning over the engine of a pickup.

This picture of the Brookside camp to the left, from coalcampusa.com, was taken in 2017 but has the look of the 1980s. Everything in Harlan except the Walmart and the fast food places seemed decades behind the times.

At the start of the 1930s “Bloody Harlan,” there was no indoor plumbing or electricity. The streets would’ve been dirt or mud. The sulfur and mildew smell that is still so strong in Appalachian water, even in hotels and restaurants, would’ve mingled with smoke, railroad soot, coal dust, gas lamps, sweat, and waste. It might not have felt so stifling to European immigrants if they’d come from notoriously overcrowded cities of the time, but it certainly would feel oppressive to native Appalachians and the Deep South workers, used to wide open lands. Certainly the coal companies wanted the public to believe that coal families were grateful to have an affordable home with a community. Regardless, isolated is isolated and these people were wholly controlled by and at the mercy of corporate interests that categorized workers as a cheap, expendable resource.

At the start of the Brookside strike in 1973, this camp still did not have indoor plumbing. I didn’t see any old outhouses (odd because so many old, abandoned buildings are left standing in Appalachia) and wondered if originally people used the creek. Workers’ quality of life simply wasn’t a priority for the coal companies – certainly not if it would dig into profits. A commission that investigated living conditions in Brookside after the 1973 strike found that the community water pump was dangerously contaminated with fecal bacteria. One investigator noted dryly that this explained the RC Cola signs posted everywhere.

How did this happen to modern American citizens? The coal companies claimed their housing offered convenience and affordability. The truth is they kept wages and benefits so minimal that miners couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. It may have been a contractual requirement, anyway, exactly like the yellow dog contracts the Supreme Court recently revived. If the reason Brookside workers had gone on strike in the 1930s or 1970s was simply to insist that their standard of living be upgraded to the minimum standard of the time, it would have been understandable. But no. First, they had to use a strike to protect themselves from being asphyxiated, electrocuted, crushed, starved, fired & evicted because of injury. Or worked to death, literally. That aside, then they needed a union because asking for human decency would get them fired, yet organizing provoked violent resistance from the company, even against women.

We think the abuses of the early 20th century are “history” but they aren’t. Look at the difference between CEO pay and worker pay today. Look at workers who hold multiple jobs because none pay well enough to live on. Look at jobs shipped overseas to exploit even cheaper foreign workers, and thus, increase profits. The world hasn’t changed much; we simply see it or understand it less.

Further, I still maintain faculty are not so different from miners in that we want(ed) the same things: to be paid at a level commensurate with our expertise and effort, to say nothing of wages competitive with regional norms, and to actually receive the benefits we pay into. We want to hold management to its promises about workload, and we want to live in the standard of our time. Sure, university faculty today have things a Harlan miner could only dream about: Worker’s Compensation, paid vacation, no threat of physical injury or death – all won for us by unions past. On the other hand, at the university where I teach, our workload continues to grow, uncompensated, and we have to cover the empty positions that sit unfilled because the university doesn't pay enough to retain faculty. Our state defunded our healthcare for 18 months, forcing us to pay both the premiums and the cost of care, and our required state pension - into which we are obligated to pay 8% of our salary each year - is constantly threatened. We saw that other unionized faculty were doing better so we organized. We faced resistance from management and stools. All of this was familiar to a miner. Times have changed … but they haven’t.

“I am not afraid of the pen, or the scaffold, or the sword.

I will tell the truth wherever I please.”

- Mother Jones

Lynch, KY

Along the winding, 2-lane road between Harlan and Lynch were a couple of small still-operating coal mines amongst the many abandoned. These survivors are all non-union now. Those who fought to organize the mines, some across multiple generations of their family, are bitter about it. The new generation – the beneficiaries of higher pay, safety, medical care, paid vacation, benefits, and so much more, won at terrible cost over more than a century – take for granted the blood and sacrifice that paved their way. This better life is simply their due, they think. They believe it cannot be taken away, and so they don’t see a bigger picture as it is nickeled and dimed away. They think they don’t need a union.

I understand this well, in that on my campus some faculty also don’t see the need for the union. Among these, typically the older faculty insist that our increasingly corporatized administration nevertheless still prioritizes faculty needs over making and saving money or rewarding itself. The younger faculty are so fearful of administrators who have for years bent policies or standards behind closed doors without consequence, they feel they cannot risk any action which might be viewed unfavorably. (This fear is a Koch and FOX news fabrication. Statistics say that management tends to hire union members more than non-members into their ranks because union members tend to be more active and capable.) Still, younger or older, too many of these faculty have no trouble accepting union-won raises and benefits, then making it known what more the union had better do if it expects them to join, someday. Yes, it’s difficult and frustrating, and it speaks to a changing moral center in our society.

The national decline in unions in the past fifty years has consequences far beyond economics, although the economic toll is what’s most visibly obvious in Harlan County. In Harlan, housing alternates between deteriorating trailers with ply-boarded windows and expansive brick ranch-style homes sporting impeccably landscaped yards. Sometimes they're next-door neighbors.

Another consequence of declining unions is community connection. A strong union draws attention to the unique needs of its community, raises scholarships, nurtures sustainability, assists with the homeless, elderly, or hungry, takes on the concerns of its community, and pressures local leaders and lawmakers to do the same.

Appalachia needs this desperately. For every fast food joint there is an emergency clinic, cardiovascular care center, or mental heath facility: signs of an overworked, poor, depressed, junk-eating population. What hope is there to get out or do better if you can’t earn a better wage, can't have enough healthcare, or build up savings – and if there’s no support even to try?

I squinted at the coal-laden trucks lumbering along the highway. Scabs. During the Brookside strike a corrupt judge issued an injunction against strikers’ using the word “scab.” It was too offensive, meaning too effective. I’m not sure how many people today even know what that word means. The implication is so much more real when you watch a lone, wheezy conveyer carrying coal past boarded up, abandoned houses.

But onward to Lynch.

I’d read about a café in Lynch and was desperate for good coffee, since there was no Starbucks, Dunkin' Donuts, or even Panera for miles around. The regulars looked up and nodded when I came in but weren’t surprised by a stranger. The café blared Christian pop music through its speakers. The napkin dispensers advertised a group that “uses horses and horseback riding to share the ministry of Jesus Christ.” It was strange, maybe an effort to attract visitors from the Kingdom Come theme park up the road. That hadn’t been mentioned in the café’s reviews, but sure, what else is there to hold onto if you’re poor, exhausted, malnourished, and hopeless?

Next to the café was the town’s old tipple. Across the street was an exhibition coal mine. Monuments and placards out front paid tribute to both UMWA President John Lewis and to the coal company’s efforts to develop infrastructure and community needs in Lynch. The texts offered a surprisingly balanced perspective.

The entryway leading to the underground tram ride was lined with large informative plaques and vintage photos about each decade since the mine opened, treating company and union concerns equally and contextualizing within national events.

The entryway leading to the underground tram ride was lined with large informative plaques and vintage photos about each decade since the mine opened, treating company and union concerns equally and contextualizing within national events.

A college-age young man drove me through a spaciously dug mine where an adult could stand upright, so it was not an accurate recreation of the cramped conditions the miners actually dealt with. We stopped in front of mechanized characters (like Disney World) arranged in “rooms,” who acted like they were digging or hammering while telling their stories of coming to work in Lynch. Each subsequent room was supposed to be about ten years later.

It was hokey but I could see this being entertaining for kids. One of the main storytellers was an Italian immigrant whose son and grandson also appeared over the course of the decades. He spoke of initial resistance to foreigners by native Appalachians because foreigners worked for less and were unknowingly imported as scabs. That hostility gradually faded as workers realized they were all in the same boat, particularly when they decided to unionize. An African American character said mining was better work than what he’d done in the Deep South, that he enjoyed the community, and he was proud of his expertise and contribution to the nation’s need for fuel and energy. Several other characters echoed that sentiment. In one of the rooms, workers whispered that they wanted to go to a union organizing meeting but were afraid of what would happen to them or their families if they were caught. Almost all the characters supported the union’s gains regarding safety and living conditions and were glad they formed a union, but disliked how often they had to be out on strike, since UMWA’s strike pay wasn’t enough to live on.

The end of the tour was a short film projected onto a rock, detailing how coal is formed and how it can be mined, combining science with the obvious pride of storyteller who loves the subject.

I came away musing that coalminers enjoyed their work. I've been so focused on their terrible living and working conditions, I'd never considered this possibility. I'd been so focused on what my own union needed to fix that I had maybe started to forget there are still parts of my job that I love. Miners organized because they wanted a better life doing exactly what they were doing and living exactly where they were. Don’t change jobs; don’t move away; change the system you’re in for the better. I knew that when I started organizing; I had forgotten it.

I happened to be the only person on the Lynch property that day, but the young man said their busy season would start in a week or two and would require 10 or more jammed-full tours every day. I didn’t realize there was so much lingering public interest in coal mining, aside from Trump’s hollow claims of bringing back the industry in full force.

The guide asked why I’d come, then if I’d seen “Bloody Harlan.” He listened to my observations and apparently decided I was for real. He said that the Lynch property was sponsored by miners themselves, and while UMWA and businesses may have contributed funding, the content was developed only by miners. He volunteers because he’s the grandson of a miner. We shook hands and he encouraged me to visit the Coal Mining Museum a minute or two down the road in Benham.

The Coal Mining Museum was a 3-story house tucked into a sleepy main street. The basement and first two floors were divided into pods that each recreated an aspect of a miner’s life: for example, one corner of the second floor looked like the interior of a coal camp church, complete with an organ, pews, and mannequins dressed as a family and preacher. There was a typical kitchen, bedroom, schoolhouse, company locker room, and various other scenes. Half of the basement was a replica of a coalmine. It was only about four feet high so this time I did have to crawl!

There wasn’t enough context, though. Which decades were represented? Was Harlan County always so behind the times? How did the lifestyle on display compare to the average lifestyle in the county, state, and region? Everything looked cleaner and in better repair than I could believe after seeing Brookside. I was looking for hints about whether this museum was the miners’ or companies’ perspective and finally decided it was a slightly pro-company exhibit, for three reasons.

First, there was a sign in front of the recreation of a miners’ shower room that detailed how nice it was that the Company gave miners a locker for their street clothes and free soap to use before going home. The soap was the size of a silver dollar. (Who needs Black Lung care or a pension when you have a sliver of soap?)

Second, everything the miner was shown to do or use looked too much like 1950s middle class Midwestern. This is how most companies wanted the public to think miners were being treated, but it doesn’t take much effort to discover how desperate and poor miners actually were.

Third, the entire top floor was a Loretta Lynn display, which I skipped. Then there was only one small corner specifically about UMWA, way in the back by the restroom. That was the only place I found a meager paragraph about Mother Jones, although miners in this part of the world would have revered her.

“There’s a fire in our hearts and a fire in our soul

but there ain’t gonna be no fire in the hole.”

- Hazel Dickens, “Fire in the Hole”

Matewan, WV

The route to Matewan wound up and down mountains on steep, angular, unrailed 2-lane roads. It was picturesque but extremely remote. I would never have found Matewan if not for Google, whose only instructions were hastily delivered directions rather than street names: “Turn left now.” Cell signal disappeared about half an hour out of town; at first I thought Google had a nervous breakdown.

Matewan itself consists of a main street with a lot of boarded up storefronts. There's a pawnshop, a UMWA office, and the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. There was no gas station or grocery store.

I met Wilma Steele at the West Virginia Mine Wars museum. She led a small group through the exhibits. One notable item was a canvas tent set up the way miners and their families would have lived in it after being evicted from company housing. Evictions might happen because they couldn't afford to pay for their house in the coal camp, or because they were caught talking about a union, or because the miner was injured. Wilma noted that miners dug pits under these tents so women and children could hide below the level of gunfire when (not if) Baldwin-Felts agents drove by and fired into tent colonies. Miners also lined up their cast iron cookware along the inside edges of the tent so that any bullets fired on an angle would ricochet and perhaps not kill someone.

Wilma gave me a red bandana to wear to the reenactment of the Matewan Massacre and asked if I knew where “redneck” came from. The striking miners who marched to Blair Mountain didn’t have uniforms. Neither did Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin’s thugs who harassed the miners, going as far as chartering planes to drop ordinances on them. (This is the only time American civilians have been bombed on American soil.) To distinguish themselves, the miners tied red bandanas around their necks, thus becoming “rednecks.” They got these bandanas from their company stores, who sold only red to better hide the blood from mining injuries.

I expected the reenactment of the Matewan Massacre to be a 5-minute event on main street (where it actually happened) but it was a costumed play in a small park, laid out like the 1987 film Matewan. In fact, it was sort of like an opera: a short scene followed by the characters’ soliloquies, with each pairing offset by a musical interlude. Miners spoke of working long and hard, fearing for their lives, but never getting ahead; the Baldwin-Felts agents spoke of not wanting to treat miners badly but “business is business” and they had a job to do; Sid Hatfield argued with the town stool & spy about ethics and morality in capitalism. Gunfire in the final scene proved too much for my little terrier so we missed the free lunch of cornbread, beans, and roasted pork.

Before the reenactment, an organizer for the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) spoke to the audience about how proud she was of these descendants of brave miners in the southern counties, who knew from generations of example that they needed to fight for their rights. These miners' descendants were the very teachers who led the way for the recent statewide teachers' strike. She passed the mic to one of the teachers, whose first words were, “I want to be sure everyone here knows where I stand. I support the union. I’m union proud. Can you say that along with me? We are … union proud!” It was such a relief to be in a crowd that bellowed those words repeatedly for each speaker without hesitation or condition. I felt hurts of the past 18 months – members who hurled threats to quit whenever they disagreed with something, or failed talks with freeloaders, or hallway sneers from stooges – start to slip away. The difference between UMWA and AFT, or even AFT and NEA (longtime rivals) didn’t matter. What mattered was when someone referenced Janus the crowd needed no explanation, and instead radiated the energy to keep fighting and keep going. It was electric and as close to that “one big union” Mother Jones spoke of as I’ve ever felt.

“The miners lost because they had only the Constitution.

The other side had bayonets.

In the end, bayonets always win.”

- Mother Jones

Charleston, WV

The path from Matewan to Logan then on to Charleston gave me access to the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek area that was pivotal in launching the West Virginia Mine Wars. The dog and I stopped at plenty of historical markers along the way. I wanted to spend a few days in Charleston, though, for modern amenities and to pause and reflect on what I’d learned and how it relates to my union life and work at home.

I have freeloader colleagues at the university who claim they are teachers first and foremost, yet can’t accept that public education in Illinois is almost entirely unionized. The oldest and largest union in this country is the National Education Association! Teachers’ unions, even in West Virginia, Kentucky, Arizona, and Oklahoma, where Republicans stripped collective bargaining rights, nevertheless rallied thousands of members and shut down public education statewide, while still, themselves, delivering food to students who would go hungry without school meals. Education and unions go together. When legislators control both their own rising salaries and their state’s decreasing funding for education, and when administrators control campus budgeting without being legally mandated to bargain with their teachers, what else is there to do but take to the streets? By focusing public attention and sympathy on the plight of funding-starved schools, disadvantaged children, and poverty-level educators, these teachers leveraged change.

A strike is not a mob. A strike is not desirable, either, but when it must happen it is the ultimate expression of democracy and the power of the First Amendment.

West Virginia was the first, so I wanted to see where teachers gathered, much like the miners in the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain. Back then, tens of thousands of men walked from southern towns like Matewan and Logan to the rally point in Marmet, and then on to the capitol grounds in Charleston: 90 miles or more. I drove that route. It was rough even in the comfort of a car!

West Virginia was the first, so I wanted to see where teachers gathered, much like the miners in the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain. Back then, tens of thousands of men walked from southern towns like Matewan and Logan to the rally point in Marmet, and then on to the capitol grounds in Charleston: 90 miles or more. I drove that route. It was rough even in the comfort of a car!

The media said “unprecedented” about today’s teacher strikes. That's myopic. What were the flood of strikes between 1880 and 1930 for, if not to educate the public about dangerous working conditions and deplorable living conditions, and thus, leverage change? It is to those brave men and women that we owe weekends, the 8-hour day, sick leave, child labor laws, and more. I am hard pressed to think of anyone I know who doesn’t enjoy what union members – coalminers, factory workers, steelworkers, and yes, teachers – won for us.

It was heartening to see that by 2002 the West Virginia legislature honored its coal history with a bronze statue of a miner on the capitol grounds. Still, they missed a major point, which is how exploiting that miner has led to so much of the state's modern economic woes. West Virginia legislators of the Gilded Age openly collaborated with robber barons to suppress workers’ Constitutional rights as well as their protests.

Ultimately, by not reigning in greedy profiteers like Justus Collins and J.P. Morgan in the 1880s-1930s, West Virginia allowed single companies to siphon the wealth buried in the mountains away from its people and state. Worse, because the governor and legislature also allowed coal operators to exploit and underpay workers, a long-term state of poverty developed. Then, when the coal industry dried up, that culture of poverty remained.

Which is more enduring – West Virginia’s coal heritage or its quagmire of exploitation and poverty?

Let’s ask the teachers who marched on Charleston this year.

Today, we have “Right to Work for Less” states and an impending Janus decision from the Supreme Court. These are attempts to put working people back into the culture of the Gilded Age a century ago, under the thumb of the same kind of robber barons and monopolies, with the same explicit support of the state and federal governments. What’s happening today, in response, is becoming the same story a Colorado coal miner could have told in 1914 or a Harlan County miner could’ve told in 1930. I wonder how far Americans today will be willing to go to put a stop to this exploitation.

“Half the town'll die from the mining of the coal.

The other half'll leave when the mine decides to close.

The people who are left will starve to death at the hands of the company store.”

- Greg MacPherson, “Company Store”

Scarbro, WV

The Whipple Company Store is about an hour southeast of Charleston. The tours are run by the woman who owns the place now (Joy), who claimed that she has both company and miner background.

The first part of the tour was on the front porch, where Joy asked me why I'd come. I told her I’m a union organizer and local president looking to reconnect with my history. She retorted, "Well, this building was designed to keep YOU out!" She explained how the coal owner (Justus Collins) was so adamantly anti-union that he equipped his coal camps with spotlight surveillance, which was unheard of, and designed the porch of his company store such that the angles of the steps and the plate glass windows allowed only a few Baldwin-Felts guards to defend it from ambush by union men.

My first thought: why would union men attack the company store, of all places? Before I could ask, Joy added that once the union gained control of the store, they redesigned the front steps and constructed hand rails. They could've done that for safety reasons, I thought, but Joy was clear that the union defaced the building because they disliked having been thwarted by Baldwin-Felts.

Right inside the door from the porch was a collection of old tools, hats, lunch pails, etc., and a dozen or more old photos of Baldwin-Felts detectives. I was starting to get a vibe.

Joy told me that most people today don't know that the detectives were usually very nice, friendly men. Now people talk about the detectives’ evicting miners from houses, but what else could they do? If someone stopped working and paying rent today, the same thing would happen. Further, she assured me that rent in company housing was based not on the size of the house or the value of the land but on the electric bill, and specifically on the number of light bulbs in the house. (This was a rare, unexpected benefit of Collins’ spotlight surveillance: his coal camp had access to electricity, too.) The company would let people swap their light bulbs for oil lamps and therefore pay no rent if the miner was hurt and needed to stay home. I wanted to argue with her about the ethics of even that, in a situation where there wasn't sick leave or worker's comp despite such a dangerous work environment. I could already see there was no point.

After the guard display there was a glass case full of rusted bullets recovered from the Battle of Blair Mountain. Joy mentioned that the government has never admitted it fired on the miners at Blair Mountain, even though these bullets prove it. A historian friend told me later that both sides used the same bullets, which were issued to law enforcement but also available to miners via surplus stores. We’ll never know whether federal troops ever fired on miners (it seems unlikely), but it’s quite provable that Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin took over the Army’s discarded plans to drop ordinances on the marching miners. That is, the Army decided against it so Chafin did it, instead.

Next was a UMWA display case full of ball caps, patches, and other keepsakes. Joy said she had to put that in because although miners were the audience she most hoped to draw in for tours, they wouldn't even come through the door unless there was a union presence. I thought that should be an indication of what it was like to be a miner and how much miners felt they needed their union. Instead, Joy added that miners insisted on leaving something for the UMWA display: "It's like they have to mark their territory, like a cat."

There was a hand elevator that still operated via a rope thicker than my arm. Joy said the middle of the three floors, only a half floor, was for inventory and coffin storage. The elevator was placed so that women would never see new merchandise coming in, since some European immigrants believed that if a woman saw a man's axe, shovel, lunch pail, or other tools before he handled them for the first time, he might be jinxed and get hurt in the mine. Thus, the company employed a crew of men to move all the materials into the building and up into storage via the elevator, being sure to handle everything individually. She claimed this was the origin of the term "manhandling" – not true but a colorful story.

The third floor, Joy said, was a private area for Mrs. Collins to use when she wasn’t at her husband’s side. Later in the tour, I saw professional-quality photos of children attributed to Mrs. Collins’s charitable belief that all mothers should have a photo of their children. This may actually have been an attempt to keep track of how many children miners had. Later, I learned that the third floor of the building may have been where women were raped if they couldn’t repay their family’s debts.

From there we went into the center of the building, boomy with a high ceiling and bare concrete floor, empty except for a few glass display cases along the wall and gouges in the floor where other display cases had once been anchored. The floor, made of a special concrete, in combination with the angle of the walls and ceiling, specifically reflected sound to a single point in the room. The clerk who stood there was a Baldwin-Felts guard in disguise, who was able to hear every whispered conversation on the sales floor. These clerks spoke all the many languages of the miners' wives but were disguised as being deaf. While the miners themselves rarely talked about the union in the mineshafts because if caught they would simply "disappear," the women assumed it was safe to discuss the union while they shopped. Thus, the company learned who the ringleaders were and what was being planned.

I cringed as Joy proudly recounted this. I began to think of Big Brother from 1984 and Gilead from The Handmaid’s Tale.

The last stop in the building was the bookkeeping area. She showed me a gigantic brass safety pin that miners used to keep identification disks affixed to their clothes, ranging from dime to quarter size and stamped with their employee number. Each time they loaded a cart of coal, they left a disk locked to the side of the cart. As the coal was unloaded, disks were collected and sorted for payment. Joy said devious union organizers would steal a key or break the lock and pull disks off so miners weren't paid enough, since nothing agitates people faster than unfair pay. (I find this hard to believe of organizers.) Joy added magnanimously that nobody could blame those organizers, since most of these workers were immigrants who barely spoke English and had to be pushed to considerable anger to risk joining a union.

Yes, exactly, I thought. Companies hired immigrant labor because they didn’t speak English and didn’t understand the politics and economics of American mining. That made them useful as scabs or to undercut wages. They did indeed have to be pushed to risk their new lives by joining a union, since they had no status or even citizenship. Companies exploited this.

On payday, Joy said, the miners picked up an envelope tallying their number of disks along with all the deductions for tools. They had to buy their own shovels, axes, dynamite, helmets, etc. There were also deductions for medical care, light bulbs, and other life expenses the company did not provide. Inside the envelope was cash for whatever pay was left. It was always cash, she insisted, showed me the bank advertisements on the back of the envelopes, along with admonishments to "save as much as you can” (must have been laughable in its time). The miners could then check the math, count the cash, and exchange it for scrip. They almost always did this, Joy told me, because it saved their having to pay taxes.

How that worked: Scrip belonged to the company, as did the company store, and the company had already paid its taxes. Cash, on the other hand, belonged to the government, which expected to collect tax whenever cash changed hands. If a worker accepted scrip to buy the company's goods there was no tax for the miner and that savings could be as much as $2 per paycheck – the same as a month's groceries. I was taking the breath to ask about inflated prices when Joy said she had stacks of fliers proving that prices at the company store were the same or better than at the local stores. I wish I had asked to see.

At the end of the tour we stood in the gift shop and talked. Joy claimed her family knew “Mary” Jones well, saying it's a shame how she's portrayed by historians as loud and crass when she was entirely sweet, gentle, and soft spoken until her children died. After that, she was only angry and looking for an outlet. Joy went on that the Battle of Blair Mountain was a tragedy because "Mary” (never did she say “Mother”) betrayed “her boys” by not treating them with enough respect to explain why she thought they shouldn't march. She simply declared and expected that to be enough. I asked if she was talking about the business with the possibly fake telegram from the president, urging miners to stop their protest in Charleston. She gave me a sly look and muttered, "Well, nobody ever proved that it wasn't a real telegram, and the way Mary handled it was just a shame." Joy repeated many times that "Mary" probably did care about the miners because she was a nice person, but didn’t care all that much about labor rights, specifically. What fueled her was anger about losing her husband and children. By the time Blair Mountain came around, she had pretty much spent her anger; thus, the collapse of her leadership and judgment.

It was both shocking and distressing to be plunged into a devious corporate perspective. Joy was careful to tell me several times that she supports unions for safety issues, but it's not that 2-dimensional. Safety, hours, respect, medical care, base pay – these are all interwoven long before a discussion of scrip vs cash, fair vs inflated prices can happen. Giving a fair business deal in your company store but oppressing the people in virtually all other ways embodies everything Ayn Rand ever wrote.

Beckley, WV

The underground mine tour in Beckley was by several accounts too company-centric to justify spending the admission fee. The site was crowded with kindergarteners that day, too, so the dog and I perused the free exhibits instead. These were individual structures transplanted from various coal camps and arranged into a single hypothetical camp. We saw a bachelors’ shanty that was about the size of my closet, family housing that was much too large and impeccably maintained to be realistic, and the exteriors of a church, school house, and supervisor’s mansion.

“Sit down and read. Educate yourself for the coming conflicts.”

- Mother Jones

Conclusion

I arranged this trip in the hope of learning more about my roots as a union organizer and officer, and of finding a renewed energy and resolve to keep chipping away at the many challenges.

It was frustrating to spend so much time in areas with spotty or no cell signal, in dry counties (no wonder these people fought so much, ha ha) where roads are in poor repair, and where highway billboards extolling the Bible are as common as ads for gas stations and fast food. It was tough to look at so much despondent, resigned poverty and isolation.

Still, it was important for me to learn how this standard of living evolved directly from the so-called “pro-business” policies of the early 20th century, known as the Gilded Age. Those policies crushed a whole population and stymied the economic, social, and cultural development of an entire region. Now, the same “pro-business” thought is resurging through the Koch brothers, the radicalized arm of the Republican party led by Donald Trump, and in some cases championed by the same populations who most suffer the effects.

The powerful message in this trip was that the struggle between labor and the wealthy moves in cycles. We are on the down side of a cycle right now, like 1900-1920, when the government openly sided and collaborated with corporate interests. We have contemporary robber barons overtly oppressing workers (like teachers today) until they take to the streets in protest. Now, as then, management – whether a company, school board, or US president – sees unions as a threat to its unilateral power and responds with negative social media campaigns, innuendo, threats of exacerbated bureaucracy, the spread of socialism (as if that’s a bad thing), and peer pressure. It keeps us miles behind the social and economic developments in Europe, not the least of which is universal healthcare. By sowing divisiveness, today’s American management hopes as it did a century ago that workers never realize the power they have in solidarity.

Management has always been slippery and devious, able to shade or hide the truth enough to seem reasonable to the public and to its own stooges. Its goal has always been to limit the influence and political power of workers to improve their lives and their community. After all, if all Americans had a decent job and minimal standard of living, that might eat into profit, or into the salaries of the oligarchy.

Undermining a union has never been limited to management, though. There have always been workers who would rather curry favor with the boss than stand with their peers. There have always been workers who see no problem with insisting a union isn’t needed while still happily accepting union-won wages, benefits, and protections, expecting their peers to do all the work and take all the risks toward making a better living and working environment. Freeloaders and stools haven’t changed at all.

As they say in Battlestar Galactica, “All this has happened before and it will happen again.”

There's hope. There's always hope. In the 1930s, Congress passed the Wagner Act and things started looking up again for workers. Even if that legislation hadn’t happened, there were still victories. Workers who were less educated than university faculty and in much more precarious living situations nevertheless made enduring changes to an entire society through the force of their unions.

If coal miners could change their circumstances in 1918, what is possible for university faculty and staff in 2018? I’m looking forward to finding out.

Monday, January 6, 2025 at 10:05AM Comments Off

Monday, January 6, 2025 at 10:05AM Comments Off  making money. Even as a child, my life expectation was simply to have a sturdy house, a dependable car, and healthcare (with a dog). For that, I’ve always known I needed a regular job with salary and benefits. I have a love-hate relationship with that job, to be sure, but that’s my income and it’s enough. It took me a long time to name myself “composer” equal to “teacher” because I never wanted my relationship with my music to be corroded by external pressures. It’s tortured enough by imposter syndrome.

making money. Even as a child, my life expectation was simply to have a sturdy house, a dependable car, and healthcare (with a dog). For that, I’ve always known I needed a regular job with salary and benefits. I have a love-hate relationship with that job, to be sure, but that’s my income and it’s enough. It took me a long time to name myself “composer” equal to “teacher” because I never wanted my relationship with my music to be corroded by external pressures. It’s tortured enough by imposter syndrome. For me, the surprise in that conversation wasn’t their rejecting my idealism, nor even saying that their work is junk. It was the naked avarice coupled with disregard for the many band directors and young musicians who will embrace that junk. People assume if you’ve risen to a high position in your field, you embody quality and seriousness of purpose. Specifically, if you are famous and sell well in the band world, then clearly you must also be a model of the profession’s ideals and standards, right?

For me, the surprise in that conversation wasn’t their rejecting my idealism, nor even saying that their work is junk. It was the naked avarice coupled with disregard for the many band directors and young musicians who will embrace that junk. People assume if you’ve risen to a high position in your field, you embody quality and seriousness of purpose. Specifically, if you are famous and sell well in the band world, then clearly you must also be a model of the profession’s ideals and standards, right? serious musical thinkers: mentors and peers in tune with the artist’s inner life and struggles. When we were together we lit up discussing orchestration or performance or creativity. Just by proximity, they challenged me to become my best. In our every interaction, which virtually never broached how we made a living or how to make a better living, I came away feeling richer, inspired, and ready to brave a kind of Work that is always messy and challenging.

serious musical thinkers: mentors and peers in tune with the artist’s inner life and struggles. When we were together we lit up discussing orchestration or performance or creativity. Just by proximity, they challenged me to become my best. In our every interaction, which virtually never broached how we made a living or how to make a better living, I came away feeling richer, inspired, and ready to brave a kind of Work that is always messy and challenging. ose while watching television” stuff from other composers, so this was not new. It’s galling every time, though. Further, I do believe this particular clinician was speaking their truth from their

ose while watching television” stuff from other composers, so this was not new. It’s galling every time, though. Further, I do believe this particular clinician was speaking their truth from their  own longtime professional experience, yet that context matters. Their career was for many years focused on incidental music secondary to a visual. In that world, faster is both obligatory and rewarded, compared to concert music where the priorities are (and should be) self-expression and innovation. Nevertheless, I could hear the wheels turning all around me in that clinic: If I go faster I’ll write more music and I’ll sell more copies, and the more copies I sell the more reputation I’ll have, and the more reputation I have the more people will commission me, and then I’ll be famous and rich just like this person, so faster faster faster!

own longtime professional experience, yet that context matters. Their career was for many years focused on incidental music secondary to a visual. In that world, faster is both obligatory and rewarded, compared to concert music where the priorities are (and should be) self-expression and innovation. Nevertheless, I could hear the wheels turning all around me in that clinic: If I go faster I’ll write more music and I’ll sell more copies, and the more copies I sell the more reputation I’ll have, and the more reputation I have the more people will commission me, and then I’ll be famous and rich just like this person, so faster faster faster! composers in the room had already reached their artistic maturity and were doing top quality work. Even that composer who plays golf all afternoon must’ve started from a genuine love of composing and a desire to do high quality work.

composers in the room had already reached their artistic maturity and were doing top quality work. Even that composer who plays golf all afternoon must’ve started from a genuine love of composing and a desire to do high quality work.

can be created while watching television is becoming a factor in its creation that cannot be underestimated. No wonder we’re still so unhappy with the quality of our repertoire.

can be created while watching television is becoming a factor in its creation that cannot be underestimated. No wonder we’re still so unhappy with the quality of our repertoire. attempt even if I’d wanted to (although I didn’t), maybe the newer generation figures freelancing is no less uncertain than any other path. What naturally follows is, “If that’s how I’m going to make my living then I want to make a good living at it.”

attempt even if I’d wanted to (although I didn’t), maybe the newer generation figures freelancing is no less uncertain than any other path. What naturally follows is, “If that’s how I’m going to make my living then I want to make a good living at it.”